Sentimental Value

Olivier Bugge Coutté discusses structuring where montages belong in the film, the importance of trust in the cutting room, and the need to include “sparkles” amid the drama.

Today on Art of the Cut, the editor of Oscar-contender Sentimental Value, Olivier Bugge Coutté.

Olivier’s is a Danish editor whose previous work includes Thelma, Oslo August 31st, Beginners, and The Apprentice, for which he was nominated for a Film Independent Spirit Award. He also won the Tribeca Jury Award for Best Editing of a narrative feature for Bridgend.

Sentimental Value is a big favorite for the Oscars and probably many other film awards this season. Congratulations on your work on it.

Fingers crossed.

Tell me about the creation of the montage that you have at the beginning with architectural aspects of the house and building up the house as almost a character in the film.

Voice-over-driven montages have become almost a signature for [director Joachim Trier]’s films. They appear in all the films that we’ve done.

The voice itself is of an elderly woman. We’re never told exactly who it is. I don’t know who it is. It could be the house. It could be a grandmother. It could be Nora as an old woman. I don’t know who it is, but we changed it during the edit.

We tried different ages for the voice. We quite quickly found out that it felt more right to have an older woman. Because if it were a younger woman, you would start asking too many questions about who is this voice coming from?

And it would look similar to one of the characters in the film, and you would start asking, “That’s probably them,” and it would be strange.

What was the purpose of the voiceover?

So the first voiceover is about the house, obviously, which is the scene of this whole drama, in the past and in the present, it is told as a school essay that Nora wrote as a kid. If she was an object, what would she be? She tells the story of “If I were the house, this is what I would experience, how I would have experienced through the time.”

What she is maybe really telling is the breakdown of a family. She tells it from the perspective of the house. I would witness this.

I would see this, I would experience this. What the house sees is the family trauma that has been passed down in the family and the consequences on the present time of Nora’s life. How her father left the family, and how the breakup between her mother and her father happened.

Then, the way that it’s cut, we still try to make it as if it were visually seen from the perspective of the house. If you had a shot from somewhere, anywhere in the house, either room or looking out of the window or looking at a door, then we would cut to that physical space before the humans entered the frame.

Then we would let them into the frame, do what they have to do inside the frame, and then leave again as if the house was there before and the house was there after. And the house is looking at the action of the people. We have some windows, but you can hear the parade of the National Day outside and the window slams.

Then you have just the silence inside the house. You have Nora and her sister running to school, and you look out of the window. It’s very important that you look out of the window first, and they enter the frame. Then they exit the frame. It becomes a little heavy and the edit not so smooth, but that’s because it’s the house looking at them.

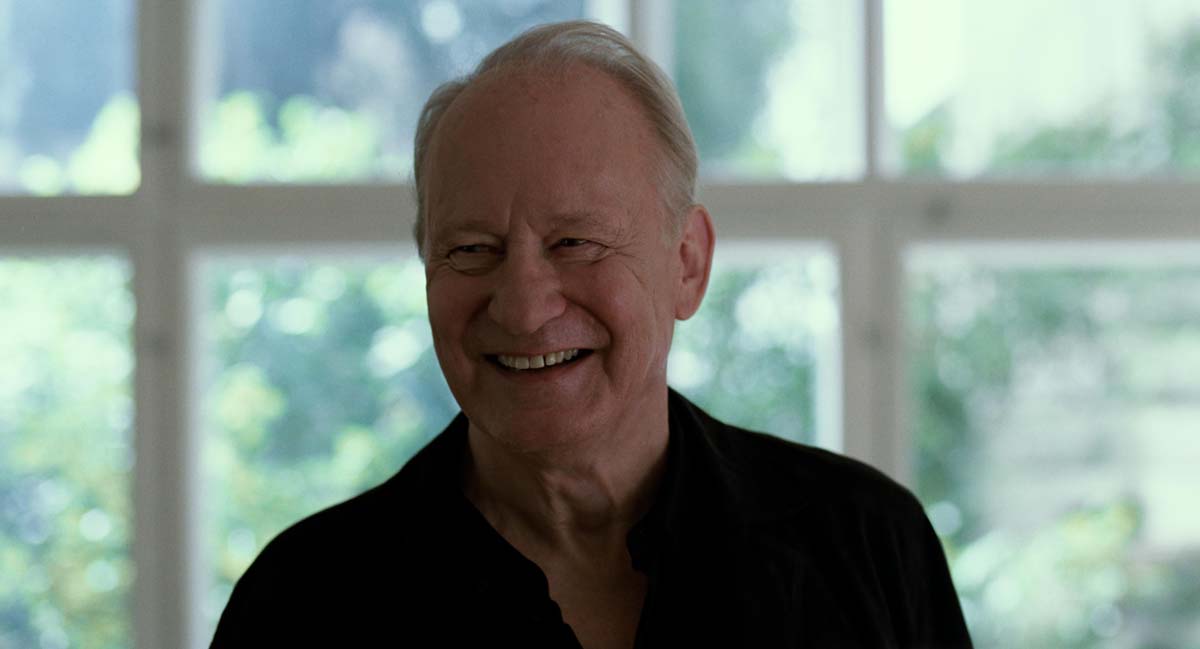

Director Joachim Trier and editor Olivier Bugge Coutté

It’s interesting that the voiceover did change quite a bit. Did the text actually change or just the voiceover talent?

Both. The voiceover was written into the script from the beginning, but they always adjust themselves according to the development in the edit. And as things are changing in the edit, the voiceover has to be rewritten.

So that’s a constant process. It was like that on all the films. I don’t remember exactly what bits in the early films, but on the previous one, The Worst Person in the World, that also had a voiceover that was completely rewritten for the opening, so they do change.

There are two voiceover bits in the film. The first opening one, and then there’s the second one later in the film about the more historical aspects of the house.

That sequence was originally way up in the beginning, so those two montages were very, very close to each other.

They had maybe five minutes in between. So much of the information was in the other and vice versa, so that had to be rewritten when they are split apart and moved further down in the edit.

I often say that a reading brain seems to be more intelligent than a film-watching brain. When you read a script, you can consume more details because you read it at a different pace, and you can stop and start. So the montages, as they are written in the script, tend to be much more detailed.

But then, when you put all those details up on the screen, people are a little bit lost. A big job of the editor is often to simplify - not just in terms of cutting down information - but trying to narrow down the psychological perspective and the narrative perspective so you know exactly what you’re telling and not telling ten different stories, so people don’t know which one to catch onto, which one is the most relevant one.

So that’s the job that happens a lot - shaping down, concentrating, focusing narratively, psychologically, then giving the right piece of information at the right time.

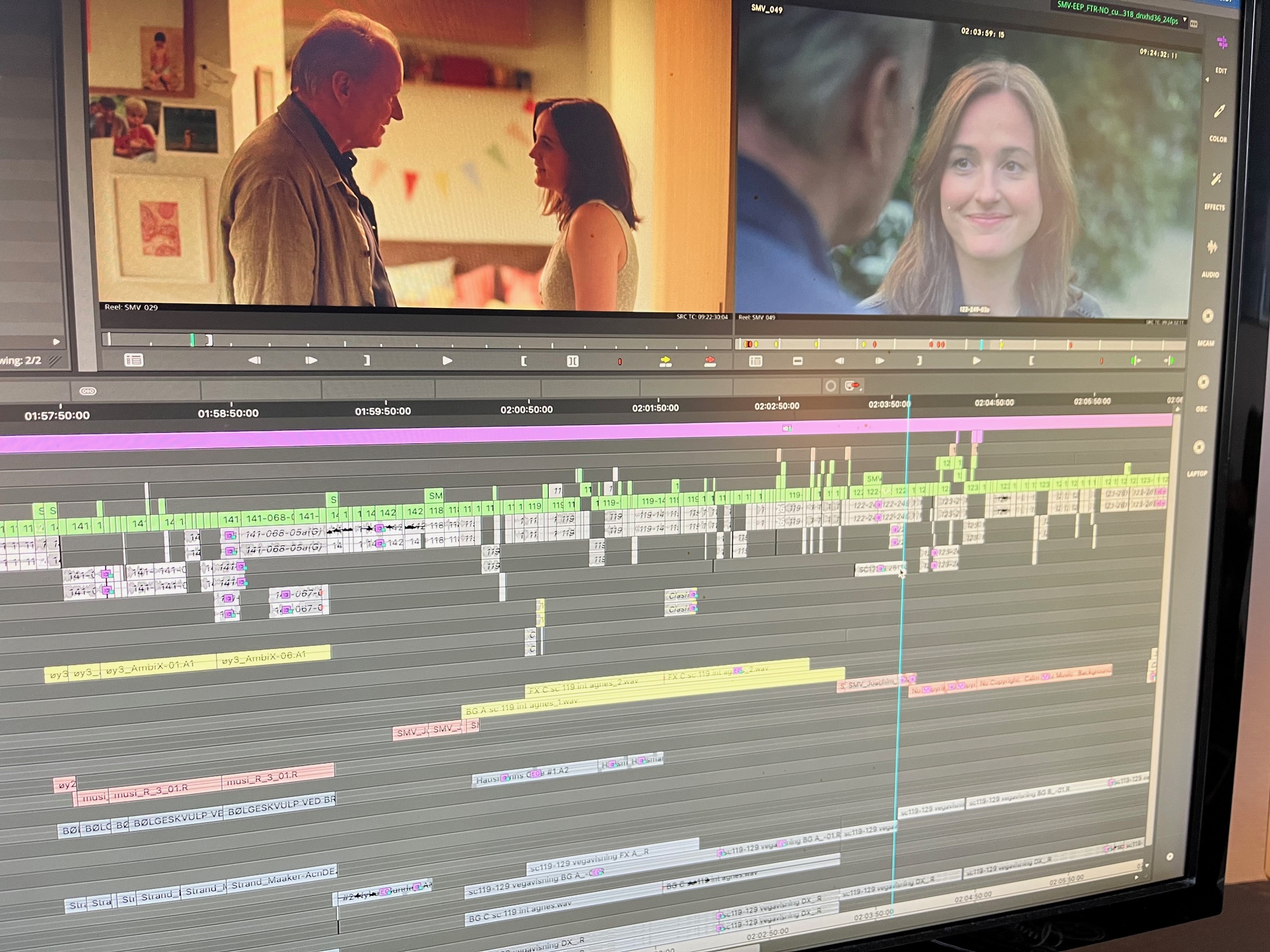

Avid editing timeline of a section of Sentimental Value

What were the conversations that you had about moving the second voiceover from being five minutes apart to being an hour apart or whatever it was?

The second montage was: we have the opening scene at the theater, she performs, and there were some extra scenes about the dead mother at the hospital, then you would have the wake and Gustav enters the house, sits down in the room before he meets the rest of the family, then he looks around in the room that used to be his wife’s psychology office and his mother’s playroom, then starts the memories or stream of consciousness memories of the history of the house, which was the second montage.

But at that point, we had not really engaged in any other characters. We didn’t know Gustav was just this person entering the room. The sisters, we didn’t know at all.

They had just talked briefly in the kitchen. Nora, of course, we knew a little bit more, but it was more from that funny sequence at the theater, but we didn’t really know her as a character, so it felt out of place to have that montage. It’s like “These guys are never going to get involved with the characters in this film.

Are they just going to have montage after montage after funny sequence after montage? Are we going to get serious at some point?” There was a feeling from the beginning that it’s not right where it is. So it moved slowly further down into the film.

At first it was in the middle of the wake after the sisters and the father talked. That felt a little bit weird then to have to come back again to the father saying he wants to see his daughter. Then it moved to after the meeting when he presented the script before they go to France.

That seemed sort of okay, but then in storytelling ways, it felt unbalanced that you have a montage and a second montage, then for the rest of the film, you don’t have any, so it’s also felt a little bit frontloaded just to have a lot of montage.

Then later on, when you maybe wanted to go in depth, some of the things that you feel that you need to understand more, then you don’t use that device again.

Also from the comments of the people that we got that that second montage would have to be later. It was a driving force right from the beginning, and it just moved slowly but slowly until it formed in place.

The evolution of the edit is so interesting to me: how sometimes you just have to have patience about when something doesn’t feel right. If it doesn’t feel right now, don’t freak out. Give it a little bit of time.

Absolutely correct. Totally agree. I like working with assistant editors because I get a lot of inspiration from them and I try to work with younger assistants so that they can sit over my shoulder and say, “That’s an old man’s cut.! You’ve got to bring that up to 2025, my friend!”

But I have difficulties in working with several editors on the same film. It’s not at all because of authority or anything. I don’t care anything about that. The best cut wins. I don’t care who found the cut.

But it’s because early in the process - when you cut a film - sometimes you do things intuitively that you can’t put your finger on completely, and you know that it’s not completely correct the way you’re doing it now, but you’re moving around something that intuitively you feel there’s something interesting in the way it’s being done in this area. I don’t know what it is. I can’t put my finger on it. It’s very fragile.

So if you come to me and say, “It doesn’t work,” I know that it doesn’t work, but I know that there’s something in it that is interesting and I will make it work. It’s very important that you have patience and you stay open to let that process happen slowly.

Then maybe at the end you’ll find out, “Okay. Everybody was right, I was stupid. It was not a good idea to take it that way.” But at least you stayed open to your voice or to your intuition.

That’s all you have as an editor. It’s your heartbeat. It’s the way you look at life. It’s the rhythm that you have in your body.

Somebody else has another rhythm, another heartbeat has other experiences in life. And they look at it. They they treat the material in a different way.

But you have to treat it in the way that you feel. If people like it, great. If people don’t like it, I’m sorry, I’ll do something.

Having known Joachim for so long - because we’ve now done six feature films together - we’re friends on a personal level. We’ve known each other for more than 30 years. Our kids know each other. We know each other’s girlfriends and wives and ex-wives and parents.

That workspace that we have created is so full of trust. I often say to other editors, and especially the assistants, that I have or students at the film school:

The most important relationship that you have to have with the director is you have to share artistically the same interests. And you have to like the material. You have to like the film, the subject, otherwise it won’t work.

The biggest important thing between you is trust. If a director doesn’t trust you or if you don’t trust him, stop immediately because that’s the chemistry that you have between you as an editor and a director when you work. And if you don’t have that trust, you will never be able to go down on a road exploring something.

After all these years in this personal relationship, we have that trust a lot. I know I can say to Joachim, “Okay, listen, just give me three hours. Go for a walk or go home and come back tomorrow. I have to try this out. There’s something here that I find that’s interesting. I know it doesn’t work, but just let me play around with this for two hours.”

And Joachim can say the same thing. He’ll say, “The thing you did yesterday - the shots I saw that you were playing around with - can you just try to be my hands for one second? - because he doesn’t know how to operate the Avid - “Of course. Sure.” So he says, “Put that there, put that here, put that here. Put the music underneath.

Let’s just watch it. Don’t say anything. Just watch it.” Then we watch it and we often say to each other, “This might not work, but it’s a stepping stone to the next thing. This might open up something.”

We did ten cuts and we wasted ten hours. And there’s only one cut that works in there, but at least there’s one cut that worked, and that one cut brought us on to the next cut. That’s the most important asset you have: it’s the trust between you.

I’ve talked to many people about the fact that even a bad idea can lead to a good idea.

Exactly.

With a bad note, you might not want to do it. You might know that it’s going to be pointless, but you still do it anyhow, because it’s going to lead to that one good cut. Right?

Exactly. I was doing a film with Mike Mills many years ago, The Beginners. Mike often said – and I quote him for that – “Random is your friend.” That’s an important thing. Sometimes you don’t know exactly why you’re doing things. I’m sure a mathematician would say, “This is not random.

This is just you not being able to explain what random is.” But, for me at least - I’m not good at math - I think that it’s random. So sometimes you do cuts and you put things together that you don’t know exactly why you did them, and it’s a little bit random.

Let’s talk a little bit about music and tone. I don’t really remember the tone of the music very early in the film, but just before you get to the title sequence, the music changes fairly dramatically to something very upbeat. Nora is trying to prepare her monologue to get into acting school and there’s a very upbeat piece of music there. So talk to me about the value of that change in music.

We often tell stories about people who find themselves in psychologically complicated places: loss in their lives, pain, and death. But we still want to make it a dynamic film full of sparkles - of comedy elements of music elements - and blended together with the heavy drama.

But we have a philosophy that if you only tell a dramatic, heavy story in a dramatically heavy way, then you will lose the audience because they will harden themselves. If you tell it with too many comical elements, then you will also lose them because they will feel distance from the drama.

And maybe it’s also because this is the way we are as human beings as well. I am like that too. I can sit and talk seriously about something and then five minutes later I jump up and put on some disco music.

We are sort of dynamic persons. We like the way that these stories are told is in a dynamic way. Changing between drama, comedy, music sequences.

They have to be dramatically interesting and actually, at the same time, if you see the second montage - let’s say you see the mother committing suicide or going to the room, closing the door, you know that she’s committing suicide.

Then a minute later you see a teenage Gustav peaking at his aunt’s girlfriend’s naked breast, and you smile and you laugh. Then a minute later the aunt dies. Then it’s a sad moment again, so within a minute and a half, you’ve been down, up, down.

It’s a dynamic way of telling a story that includes you because you don’t harden yourself. You don’t distance yourself because it becomes too funny, comical.

You open your heart with a comical element and you jump in there with the drama. The music change at the end of the first montage is an example of that. It’s the play between dynamics that we love so much.

I love the dynamics of editing and often compare it to music.

I’ve said before that if you want to make a record, you have to make sure that you put catchy tunes both on the A-side and on the B-side. You can’t put all the catchy tunes in the first 15 minutes of the A-side, because then people will never get to the end of the B-side.

Let’s talk a little of building tension. I definitely felt it as we come out of the title sequence. Nora – one of the main characters of the film - is having a little bit of a panic attack or stage fright, and the audience doesn’t know whether she’s going to go on stage or not. You just built up a lovely amount of tension before she appears on stage. Can you tell us a little about about how you built that tension? How you took the tension that was in the script and in the performance and amplified it in the edit?

I noticed something in the way that I often cut scenes because I noticed it as I was cutting this new film. In the current film that I’m working on now, I have a person walking in an empty street looking for people in the village, and he looks up into a window, into one house, into another house. It’s shot in a way that the guy in the street walks in the street, looks in the window, walks and looks on the other window.

The way I cut it, I don’t cut him walking down the street, looking around, looking up at the window. I cut when he’s already looking inside the window, leaving the window and then starting walking, so I cut in at the peak of the action.

I love doing that because it motivates the audience’s brain to start working, because they’re cut into the middle of an action and they have to stitch together: “What happened before that?”

They have to imagine that this guy entered the street and now walked up to the house and looked into the window. So they have to start using their brain and imagination about what happened.

The same with the sequence with Nora on the stage. That whole scene started with a much longer introduction. You had the external shots of the theater, you had people arriving, checking in their coats. You had a long, complicated pan on the stage, which was black before the audience is sitting down.

You would start hearing somebody - her heavy breathing because she was a little bit nervous - then you would have some stage people backstage, people that would be looking for her.

You would see that she walked off stage and you could see that they were sort of thinking, “Where is she going?” The plat is going to start soon, so you’re building up, building up, building up, building up.

So when you cut to her sitting and hyperventilating in her room, the tension was out because you had prepared so much for her nervous breakdown that - as an audience – you were already half there.

So actually, very early in the editing process I cut to her face straight up panicking, and you’re engaged! Immediately, you see a face.

You don’t know where you are. You know that it’s her. You recognize her. She just told you that she wants to become an actress. You don’t know if she’s acting or where you are, but slowly you discover the scene, so the tension hits you in the face right from the beginning.

The tension was built by cutting out the stuff that was killing the tension.

Exactly. Then we extend the moments. Once we have established the tension at a high peak, then it takes a while. She wants to get a slap from her colleague backstage to get back on, then you have more patience to build the tension for her second breakdown and running away and tearing her dress apart.

I always felt like you were coming in - not too late, but as late as you could – with scenes, and often cutting out in the middle of a conversation or before a conversation would end. The stage performances are a good example, right? She would start to perform, and then boom, you don’t have to see her performing for two hours.

There were two other scenes of her performing in the theater.

I was going to ask how much you are trimming to get to that point of coming in as late as possible and getting out as early as possible.

It’s difficult to verbalize concretely because it’s a feeling that you have in your body, and every editor has a different feeling and a different pace. We all have different heart rhythms.

This film could very easily be too sentimental. This film could very easily become dramatic at a point that it would be overly emotional.

You have to be careful as well not playing it too far with too strong music and let the scenes go too far, because they cry a lot.

Everybody’s crying in this film, at least once. Several of them are breaking down a couple of times. You can easily fall into the over-sentimental if you don’t treat the scenes a little bit hard. That’s one side, but it’s also to keep the audience engaged. It’s a balance.

It’s difficult to make rules, but it’s a constant game of giving enough to have people engaged, but not too much to satisfy the audience and the emotion of the feel of the scene, because then you will not have anything left for the next scene or for the next step in the character’s development. You shouldn’t satisfy them until three minutes before the end credits. That’s when they should get the dessert.

I’ve heard it also described that in getting out of a scene, the scene should end with a comma, not a period, because then you’re maintaining the energy into the next scene instead of killing it then having to get the energy back up on the next scene.

That’s a good way of saying it.

You use a couple of hard cuts to black. What’s the purpose or value of a cut to black?

Our previous film had a lot of cuts to black and titles. We often say that his films have a more essayistic structure, meaning that on most films that you see that don’t have black holes like this, all scenes are like cause and effect after each other.

So you have one scene that leads to this, that leads to a reaction. They’re interchanged constantly. You don’t stop the film and go somewhere else.

In literature that’s very different. You can easily - in literature - follow one character for five chapters: go to the supermarket with him. He meets another person - cut to a new chapter – for 150 pages you follow this new character.

Where does he come from? Who is he? What is his background? Five chapters later - 150 pages later - boom. That’s why they met in the supermarket.

Then you go on to the story again as you left it 150 pages earlier. That’s a little bit more difficult in film.

Classic dramaturgy in films is that everything should be chained together. And if you wait for too long before you get the answer to a scene or to a set up or to something that happened at minute 20, then you will start saying, “What happened to this character? Why? What happened to this problem? What happened to this story? I’m lost now!” By using cuts to black, you tell the audience, “We know that this part and this part are not exactly linked.”

You reset time and space when you cut to black. So when you come back up from the black, you can go into the past. You can go into the future. You can go on a side story.

If you look at The Worst Person in the World, you have a five-minute side story about how the new boyfriend met his ex-girlfriend and went to a campsite up in the mountains and she fell in love with the reindeer.

And you can go on complete side stories and disappear because the cut to black creates a new chapter, then, back on the main track.

There’s a scene when the father is presenting the script to Nora and that he wants to have her to be in his film. They’re sitting in a restaurant and he’s showing her this script. That scene has such a great sense of unease to it. You can feel Nora’s discomfort with her father. Can you talk about sculpting that kind of a performance? Or looking at the dailies and deciding when to be on each person or when or how to find the best moments?

When Joachim shoots, he has few takes, but many angles. He can easily have 4 or 5 angles for a scene. Unless it’s super complicated or something’s going wrong, he wouldn’t have more than 3 to 5 takes on each angle. It still makes for quite a lot of material.

Because of the way that he shoots, he doesn’t improvise. What is improvization? That’s a complicated discussion. Even Cassavetes, who was called the biggest improviser, didn’t improvise on set.

Joachim lets the actors move freely around a fixed path so you get many colors and variations of the same line. There’s a strict path, but the colors change from take to take.

The amount of combinations becomes big, particularly on this scene. There were at least 4 or 5 angles. It’s almost the most boring way of cutting it. It’s shot on both sides, one on him, one on her, a close up on her, close on him.

Then a wide shot from the side. That’s all it is. But the most important for me is the presence with the actors - with the drama that is unfolding, especially in a scene like that.

It’s so important to be close to the eyes, close to the psychological millimeter development in how they read each other. He’s saying something that he thinks is getting her attention.

She takes it first as a positive thing, then almost as an insult. It’s to follow the very careful psychological development.

And often when I do that, I find it difficult to change angles. I even find it difficult to change takes because I can feel the color difference between take four and take five.

If I decided to use take four - because I watched it and I love big part of it - then I can feel immediately if one line on her has been replaced with take five.

I can feel it immediately, but the consequence is that I have to live with an inferior line from take four, rather than replacing it with a better line, but with a different tone from take five.

So it’s very important for me to stay within the psychology space between them. And you often do that by using a few takes.

I dislike using the word “establishing shot” because I think it puts down the shot. Let’s just call it “wide angle shots.” We often use the wide shots not as the first cut.

Of course, we sometimes do to establish the place. So they walk in here because otherwise sometimes you get lost in geography, but we often use it in cut 5, 6 or 7 because then it becomes more of a psychological space rather than a geographical space - just explaining “this is where they sit.”

In the scene where he presents the script, I recognized that you use the wide shot in that scene, not at the beginning, but about halfway through. What was the purpose of using that wide shot at that moment?

I think it’s the moment where the waitress comes in with the coffee, so that helps a little bit, but it’s also the turning point of the scene.

Up until that point, father and daughter haven’t seen each other for a long time, and it’s been superficial things that they’ve been saying to each other: “How’s it going?” and blah blah blah.

Then comes the coffee. Wide shot. Second chapter. Nora asks, “What do you want? You wanted to meet. Why do you want to meet me?” So it’s also a way of raising the curtains there.

Also, it starts to feel like they’re in opposition at that point. They’re opposing each other and now they’re on opposite sides of the screen.

Exactly. The wide shot has a more psychological effect than being just descriptive. Had I put it as the very first shot, you wouldn’t have noticed it. Then you would just have thought, “Okay, they sat down and now I know where they are.”

Do you have another example?

The other example is the scene where Agnes comes to Nora in her apartment. That had many other angles as well.

I don’t remember exactly how many, but what I do remember is that the moment which was going to be the big moment when Nora reads the script and suddenly realizes that the monologue about breaking down and praying to God is something that she has done in her life, and realizing that this is not a script about Gustav’s mother, but maybe a script about a character similar to her or maybe it’s about her, actually.

Then she breaks down and the sister witnesses it. That was supposed to be in a long tracking shot on the side, going in slowly on her, then when she realizes and started crying, the camera would have been close to her face.

But already in the first version of the cut - and Joachim agreed immediately when he saw it - we never did a version with that tracking shot.

If you notice the way our team shoots dialogue scenes, the actors look very close to the camera. In classical - or maybe a little bit older film language - you would have an angle of 30 degrees when people sit and talk to each other so they look a little bit more past the camera, but with Joachim they look almost in the lens, so you really feel the presence of the dialogue scenes. It’s only two takes.

The two actresses are outstandingly, amazingly good. That’s none of my work, of course, I’m just accommodating how good they are. I simply couldn’t go away to any other takes from the side. I didn’t need a tracking shot to tell me, “now it’s becoming important.” Much better just to stay inside the psychology of the drama with the two girls.

In the grammar of cinema, that tracking shot is so obvious to an audience that “this is important. This is what they’re thinking about.” But with the acting in this scene that’s like a hat on a hat. It’s too much.

Exactly.

There are a bunch of jump-backs in time. Can you talk about doing those jumps in time? And when you do them, what’s guiding you to say, “This is the moment in this edit that we’re going to jump?” An example is when we go to the film retrospective and Gustav sees the performance of his daughter on the train. Though, I didn’t realize that that was a movie. I thought it was a flashback to her as a little girl, originally, then I figured it out quickly.

We had that discussion.

It engaged me. I thought, “That can’t be Agnes because it’s the 1940s and it’s Germany. Then shortly after that, it’s revealed that Gustav’s watching this film in a theater.

You have to realize that whole sequence of Gustav going to France was cut to the bone. We don’t make scenes sloppy, but they still have elements that will go out later, but the first version about that whole French sequence was 26 minutes.

Just looking at that from the minute count intuitively felt it had to be cut down. We can’t stay away from Nora for 26 minutes. The gut feeling was that it had to be cut down by ten minutes. It took quite a bit to find out what needed to go out.

The French part started with Gustav arriving at the festival, seeing Rachel from a distance, hearing her backstory, that she was a blockbuster actress, had done an independent movie that had done badly, and now she was a little bit lost about what she was going to do.

So she was open to new things. All that was cut out for different reasons but Rachel’s character was trimmed down a lot because it’s a challenge to balance four characters up against each other.

You can add a certain amount of conflicts and psychological entanglements and side stories into a film up until a certain point.

Then it becomes like zero sum game. If you add to one, it would take away from another. So if you want the story of the two daughters and the father to be strong, Rachel’s character had to come down. She had to be trimmed heavily. So that’s where we found those ten minutes in the French part.

I don’t mind people not knowing where we are going for a moment, but I want them to know that somebody is holding their hand. If you’re walking in the dark alone, then you are lost and then you will trip on something.

If you walk in the dark and somebody is holding your hand and you can feel it, that person is leading you somewhere, then you feel secure and think, “Okay, at some point somebody will open the door and there’s going to be light again.” That person with the hand holding you, that’s the editor.

So I’m happy that, people sometimes feel lost in the dark as long as they can feel my hand that is holding them and guiding them.

That’s definitely how I felt. I loved that scene. Especially the little girl’s performance on that train was incredible. That could’ve been the whole movie right there!

I agree! That shot alone is a short film! How did he pull that off? It’s shot inside a train. It’s not even a truck or anything. It’s a real train. Starting with the Germans outside, then going inside.

I don’t know if you noticed, but there’s a butterfly flying in there. The butterfly was cooled down. So when you freeze a butterfly, they slow down, as if it’s winter.

Then when you heat them up, they start flying. There was an animal handler, obviously, that keeps it cold, puts it on the side of the window, and then, when the shot starts, it heats up. And when the camera pulls back, the butterfly flies up.

That’s great. My eye was too concentrated on the little girl’s performance, which was fantastic.

I wanted to talk about another montage. It felt like a montage that might have started out as multiple scenes, separate scenes, and I want to hear from you how it evolved in the edit. It’s the “stage-fright therapy” montage.

That was a tough cookie. That was many scenes in there. They changed order many times. It was a scene where Nora is explaining to her sister that she got a warning from the theater. She tells her sister why she reacts like she does before a performance.

It’s not because she has stage fright as such. It’s because it’s the way that she opens up her emotions to receive the character and that has consequences for her psychological well-being. She tells her sister that. Then her sister says, “Sounds like torture.”

And Nora says, “No, I love it. It almost feels like by playing other people, I can treat myself psychologically.”

Which, of course - knowing Nora - is wrong, because that’s maybe just putting the psychological treatment somewhere else instead of looking at yourself. But she tells this as an insight into her character.

Joachim and I were at film school very inspired by a French director called Alain Resnais, and his film, “The War is Over.” In that, a man visualizes some women that he’s going to meet, and then he cuts between many different women in a sequence, which was very beautiful.

There was a sequence very similar to that inside our sequence in the movie, with Nora saying that she wants to be other people. Then you see boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, the same action of many different women.

That became a little bit too complicated. It’s a weird mix now of a montage that is leftover of other ideas and some of the scenes of her acting on stage are the things that we cut out from the beginning, then we put the jazz music underneath.

I’m happy that if you liked the sequence, because it’s a little bit clunky, but we love it because it, it has so much a feel of the Nouvelle Vague/French New Wave feel a woman sitting in a beautiful sunlight with a beautiful sunset, smoking a cigarette, looking out.

Jazz music comes on. People love each other. Fast cuts, jump cuts, montage. It’s silly, but we love that language.

Shoe leather is an Americanized term for when you show someone going from one place to another – walking or driving, traveling In this film, my example of that is there’s a point where you show a librarian or an archivist going down through a hallway and looking for books. What is the value of showing that, when you could just cut to the sister receiving the materials and starting to read?

Good question. The things that are normally that are often trimmed out in our film, like in many other films, that’s part of the editing revolution, is often exposition scenes. So if you look at the material that we cut out, I’m sure it’s the same.

We have a lot of exposition that is taken out because we want to let people explore the drama and not be told set-ups all the time. But you need those exposition things sometimes. When you have too much exposition, you want to get rid of it. When you don’t have exposition, the audience thinks, “I don’t know where I am.”

This place, the National Archive, and the reason why we see “the librarian” walking down to get the files is because it’s a very special place in Norway. It’s deep, deep inside the mountain. It’s the whole national archive and history of Norway.

It can be bombed, there can be disasters, there can be Mars attacks and nuclear war, and it will still be down there. So that’s the reason for that. It’s a very special place.

Originally, there was a sequence before it of a truck driving all the way down inside the mountain. You see that the doors are a half a meter thick.

Of course, it serves the purpose to say that this is the history of Norway. It’s a trauma that hits one family, but it’s also a trauma that has hit the whole nation because of the Nazi occupation and the Second World War, and the torture of the Jewish people in Norway and the left wing, social Democrats and people that had resistance to the German occupation. We had that in Denmark as well, but in Norway they really saw it.

I had a wonderful discussion, and I really thank you for talking to us about this film.

Thank you so much. It was wonderful.